MoneyGram finally found a buyer last month after years of being on and off the sales block, but it left the door open for another suitor to arrive by a March 16 deadline.

Any would-be purchasers would have to top a hefty $1.8 billion proposal offered last month by Chicago private equity firm Madison Dearborn Partners. And more importantly, they’d have to have a plan to transform the 20th-century money transfer company into one that can compete with young fintechs making it faster and cheaper to digitally send money around the world.

Just before Dallas-based MoneyGram announced its sale in February, there were reportedly "several interested parties" courting the company in January, analysts at William Blair told investors in a note after the deal was announced. It noted that the Chinese firm Ant Financial (an affiliate of Alibaba now known as Ant Group) and Leawood, Kansas-based Euronet Worldwide were among interested buyers in recent years.

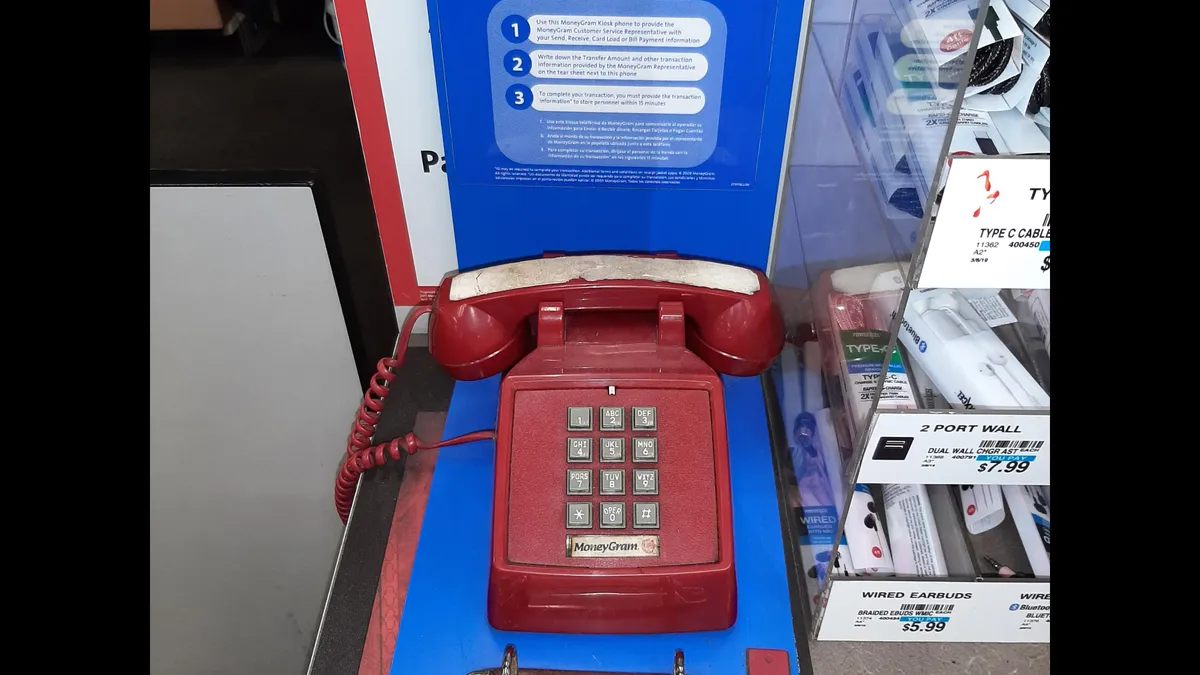

For migrant workers and relatives spread in faraway lands, money transfer tools are lifelines for sending earnings back home. Senders in countries with strong economies, like the U.S., are often regularly passing a couple hundred dollars to relatives in countries with poorer populations.

Faster, cheaper business models

New digital transfer providers often offer cross-border transactions that deliver money in seconds, whereas legacy business models may take hours, or even days to arrive. MoneyGram's website says transfers are "typically ready for cash pickup within minutes after the transfer," though that may vary based on a branch's hours of operation, the destination country and local laws.

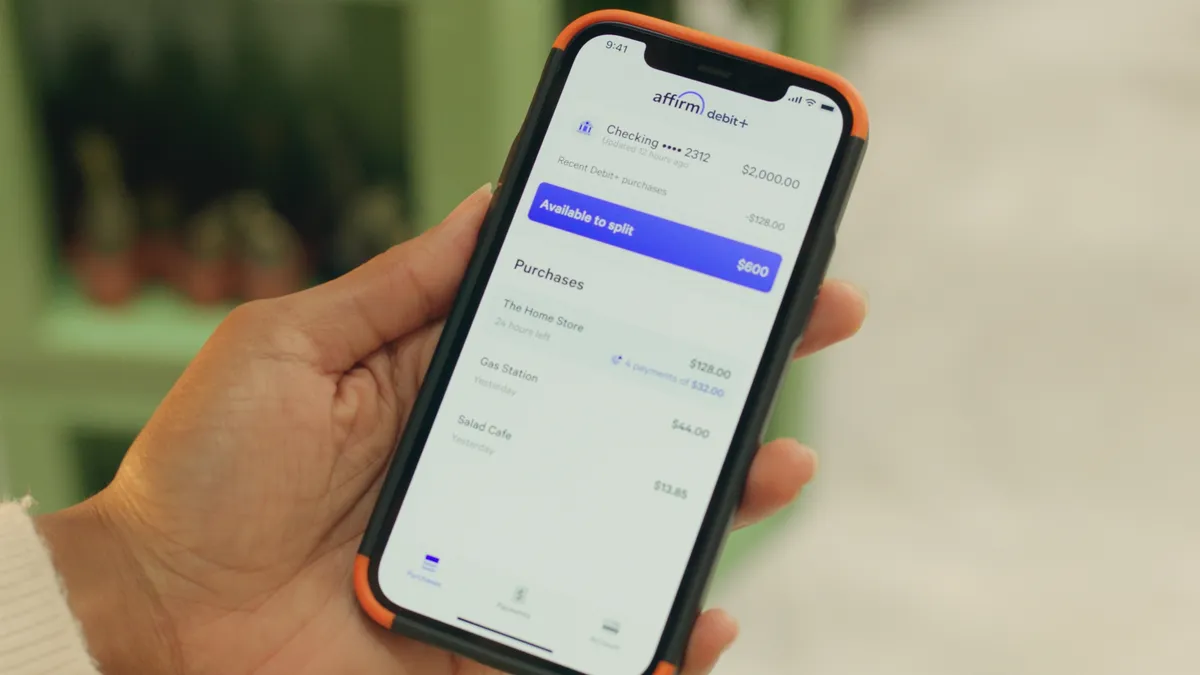

While MoneyGram and rivals like Western Union have been accustomed to charging fees of as much as 3%, the fintech rivals are charging a fraction of 1%, said Vikas Shah, an investment banker with Rosenblatt Securities who focuses on payments and fintech.

So, new fintech players, such as Wise, Paysend and Remitly, among others, are undercutting historical fees and profits in the industry.

"The new models are going to obliterate a lot of intermediaries, and MoneyGram’s business is exposed in my opinion," said Shah, who doesn’t have any clients involved in bids for the company. "MoneyGram is not really known for technology and this industry has become a technology game."

That said, MoneyGram sits in the middle of an increasingly hot cross-border payments sector. And its operations in some 200 countries, its licenses in those countries and a "big book of business" in those markets are still valuable assets, Shah said.

Paysend Chief Strategy Officer Jairo Riveros agrees with that notion, saying in an interview that MoneyGram and its old school peer Western Union have "excellent coverage worldwide." Still, he said he hadn’t heard of any other potential bidders for the company.

Costly worldwide infrastructure

Unfortunately, that infrastructure, including branch locations and staffs all over the world, also work against the company in terms of costs. MoneyGram had 898 employees in the U.S. and 2,174 employees across the world at the end of last year, according to its annual filing with the Securities and Exchange Commission. "They’re too asset-heavy," Shah said.

To be sure, MoneyGram has been working to catch up with its nimbler rivals. The company's management has pledged to increase its digital business contribution to revenue to more than half by 2024, versus 22% percent currently, according to William Blair’s note.

That's because management has acknowledged those digital customers are better long-term prospects and provide a higher profit margin relative to the "traditional walk-in customer," the note said. About 100 countries, or half of those that it serves, were digitally-enabled as of the end of last year, the company said in its annual report.

Despite MoneyGram’s "strong global brand," the business has been beset by regulatory headwinds, challenged by competition and burdened by a "stretched balance sheet," though it improved its capital structure last year, the William Blair note said. The company had about $800 million in outstanding debt as of the end of last year that would be refinanced by Madison Dearborn as part of its acquisition.

"We note MoneyGram’s enterprise value remains well below digital-only private peers," the William Blair note said.

William Blair didn’t mention any other potential suitors. A spokesperson for MoneyGram declined to comment beyond the Feb. 15 press release.

The company noted in the release that the price offered by Madison Dearborn is a 50% premium over MoneyGram's stock price in mid-December, before media reports about a possible deal began swirling in the market. It was only a 23% premium relative to the day before the acquisition was announced.

"I don’t anticipate MDP’s acquisition bid to be reversed in favor of another competing offer," Zach Spellman, who tracks industry acquisitions for The Strawhecker Group, said by email. "Unless there are external factors that prevent the approval of this deal, I suspect that this will play out in full. There may be other offers or opportunities that MoneyGram considers during this time; however, MDP’s bid of a 50% premium is pretty competitive."

Will MoneyGram become a buyer?

The Madison Dearborn managing director heading up the acquisition, Vahe Dombalagian, didn’t respond to an emailed request for comment.

"MoneyGram is a leader in cross-border payments with one of the strongest brands and reputations in the industry,” Dombalagian said in the press release. The transaction is expected to be completed by the end of the year.

For the past five consecutive years, MoneyGram has reported annual net losses, with the net loss last year widening to $37.9 million, from $7.9 million, according to the company’s latest earnings report last month.

The problem is that MoneyGram has tended to cater to customers who walk into a branch and use cash, but that’s not a growth business, Shah said.

Shah isn’t ruling out the possibility of more bids for MoneyGram. Some digital players could be attracted to MoneyGram’s worldwide infrastructure, but its technology is a turn-off, he said. "They have not kept up and that’s really the reason why the business is hurting and the business is on the block," he said.

Private equity firms like Madison Dearborn are all about fixing such issues and finding a way to bolster a business, so the company can be sold later at a profit, either to another company or in a public offering. One move might be to buy a smaller digital rival, Shah said.

Maybe with help from Madison Dearborn, Moneygram will become a buyer as opposed to a seller.