The year was 2020. Paul Kesserwani’s then-girlfriend (now wife) left their home in San Francisco to be near her family in San Diego. Kesserwani wanted to help her furnish her apartment, but was strapped for cash — he was saving for a ring — so he, for the first time, turned to buy now, pay later.

He financed a mattress through Klarna, a Ring doorbell through Affirm, and a slew of household items through other BNPL providers.

“After three purchases, I was like, ‘I have a computer engineering degree and I have a team of PhDs and I can't for the life of me stay on top of these freaking payments,’” he said. “This is so confusing.”

At the time, Kesserwani was running Cushion, a fintech that had offered automated overdraft fee negotiation since 2016. The venture was successful, refunding millions in overdraft fees up until that point.

Following his first foray into BNPL customership, Kesserwani and his team dove into Cushion’s customer data and found out that customers were leaning heavily on BNPL, not just for large, one-time purchases but to finance DoorDash meals, Uber rides and grocery lists.

“[We] realized this was about to get so urgent, and no one was paying attention,” he said of customers’ short-sighted BNPL habits. “So we dropped our thriving first business ... and decided to go all-in on bill pay for the BNPL era.”

The average BNPL customer has four concurrent BNPL loans, according to Bankrate. And, according to data released by the Federal Reserve Bank of New York this week, many BNPL customers are “financially fragile” – meaning if they had to come up with $2,000 in the next month, they couldn’t do it.

BNPL is a tool used across financial profiles, at least to a point: 14.6% of those surveyed by the Fed with an annual income above $150,000 used BNPL; and 11.6% of people with a credit score above 760 used it.

BNPL take-up rates, however, are notably higher with those whose credit scores are 620 or lower, for those who have been 30 or more days delinquent on a loan in the past year, and for those who have been recently rejected for a credit card. BNPL use goes down, too, when looking at higher income brackets; and when looking at higher levels of education, Fed data shows.

According to Bankrate, more than half of BNPL customers surveyed report having fallen behind on payments.

Switching focus

When Kesserwani and his team had their revelation about BNPL, what Cushion had been focusing on was fighting with banks, rather than addressing the root cause of why their customers were overdrafting in the first place.

By digging through “hundreds of millions of customer transactions,” it became clear what the root cause was: cash flow, or lack thereof. And it became clear that, in the last 20 years, the landscape of consumer bill pay had completely changed.

“Twenty years ago, you had your car payment, your rent, your credit card, and your phone bill, and it was straightforward. Then in the 2010s, subscriptions became a big thing, so now you had to factor in your Netflix, Hulu, Tinder … and that's another five to eight payments you need to make each month,” Kesserwani said.

And in the last three to four years, he noted, the shift was in BNPL: adoptions of the tool completely exploded.

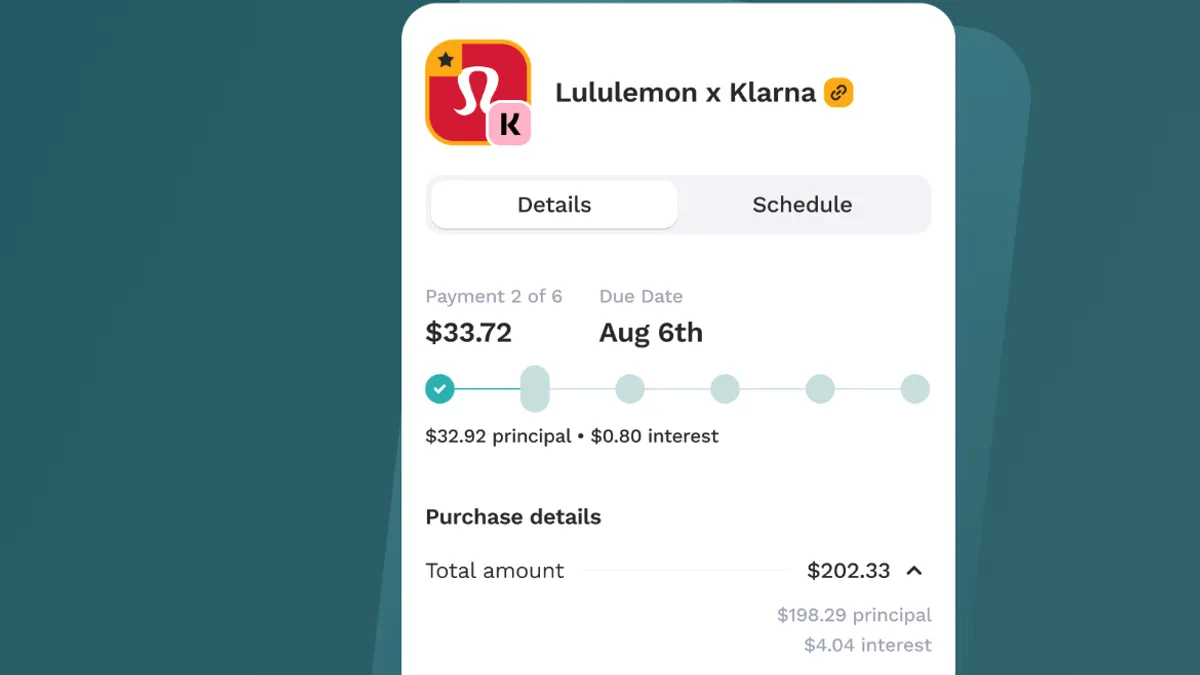

“BNPL is unique in the sense that it's not just a payment you make. It’s a loan with a bunch of characteristics: paying four versus paying six versus paying 12 [installments]; this one has interest, that one doesn't; this is due weekly, that's due monthly. Stacking just two or three BNPL loans by themselves is unmanageable, let alone putting that on top of the tower of subscriptions and other bills,” he said.

“As [bill pay] is getting more complicated, consumers are making more mistakes,” he said. “[We decided to] focus on consumer bill pay — and in that, let’s really focus on a solution for this BNPL era.”

Shifting focus when Cushion was in its prime may have seemed counterintuitive. Kesserwani said it wasn’t easy to let it die and start from scratch, but creating a tool that would help customers get on top of their BNPL loans, along with other monthly account draws, was “urgent,” he thought.

To aggregate a consumer’s bill and subscription payments into Cushion’s feed was easy with Plaid, a popular fintech that gets real-time consumer financial data through contracts with banks and the use of screen scraping.

But aggregating BNPL payments into a feed required engineering on Cushion’s own part.

“These BNPL operators have no [application programming interfaces], and they're very hard to scrape because they don't use username and passwords. They use phone-based authentication,” Kesserwani said. “All of us became BNPL customers to better understand the landscape, and we learned that they email you — they email you, ‘Hey, your order’s confirmed;’ they send you another email, ‘Here's your loan ID;’ then they send you another email and another email. ... So we hired a team of PhDs in machine learning. They figured out a way to reconstruct all of your loans based on just looking at your email inbox.”

Challenges there included a rigorous multi-month audit by Google, to gain access to customer Gmail inboxes; and further, navigating the “sloppiness” of some smaller BNPL operators who might not even send a loan ID via email.

“It turned into a full time job for a whole team for two years to finally build out the system the way we needed to,” he said.

A revamped Cushion was launched earlier this year.

Credit assistance

Kesserwani explained, with emphasis, that he’s “not anti-BNPL by any means.”

“I use it all the time,” he said. “But consumers do not have enough guardrails around it.”

Most BNPL providers don’t report to the credit bureaus. That means when BNPL providers lend to a consumer, they’re doing so without a complete credit profile.

“Say I get a loan from Affirm for $800. If Affirm doesn't tell the credit bureaus about that, then Klarna goes to underwrite me, and I appear creditworthy to them, but they don't know about my $800 Affirm loan. Then Klarna gives me a $500 loan, [which] they also don’t report to the credit bureaus; and before I know it, I’ve now signed up with seven different BNPL companies, all of which have a limit to how much they’re willing to lend [me] … and all of which underwrote me incorrectly,” he noted.

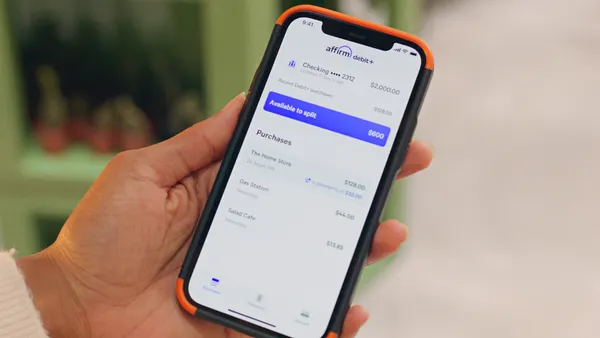

In addition to its BNPL and bill aggregator, Cushion offers a credit-building virtual payment card. For between $4.99 and $12.99, customers get a virtual payment card number that they can provide to billers and BNPL providers. Cushion reports their payments to the credit bureaus monthly, thus helping customers build credit.

Customers simply must change their preferred payment card within a biller’s system. On the back end, the Cushion card pulls directly from a customer’s bank account or debit card.

When consumers find out their BNPL payments aren’t being reported to the credit bureaus, they think, so-says Kesserwani, “’Well, wait a second, I'm taking a loan, and I'm paying it back on time. Why am I not getting credit for doing my end of the bargain here, which is to pay back my loan?’”

“We have a system now set up where we're able to report those payments to Experian, and we're in talks right now with TransUnion and Equifax,” he said.