In early 2022, then-PayPal CEO Dan Schulman had high hopes for the company’s Venmo brand. The peer-to-peer payments tool delivered $900 million in annual revenue for 2021, and income was expected to keep surging the following year.

But today, it’s anyone’s guess how much revenue Venmo is contributing to the company because PayPal hasn’t disclosed that financial data for the unit in over a year.

PayPal acquired the popular person-to-person payments tool in 2013, as part of its $800 million acquisition of Venmo parent Braintree, back when former PayPal parent eBay was calling the shots, with leadership from PayPal President David Marcus.

PayPal has been promising to capitalize on Venmo ever since. The brand is seen as a calling card for the highly coveted millennial and Gen Z sets, which have been using it for years to send payments to friends and family, pay the babysitter and split a dinner tab. The snag for PayPal: the app is largely free of charge for its 90 million users.

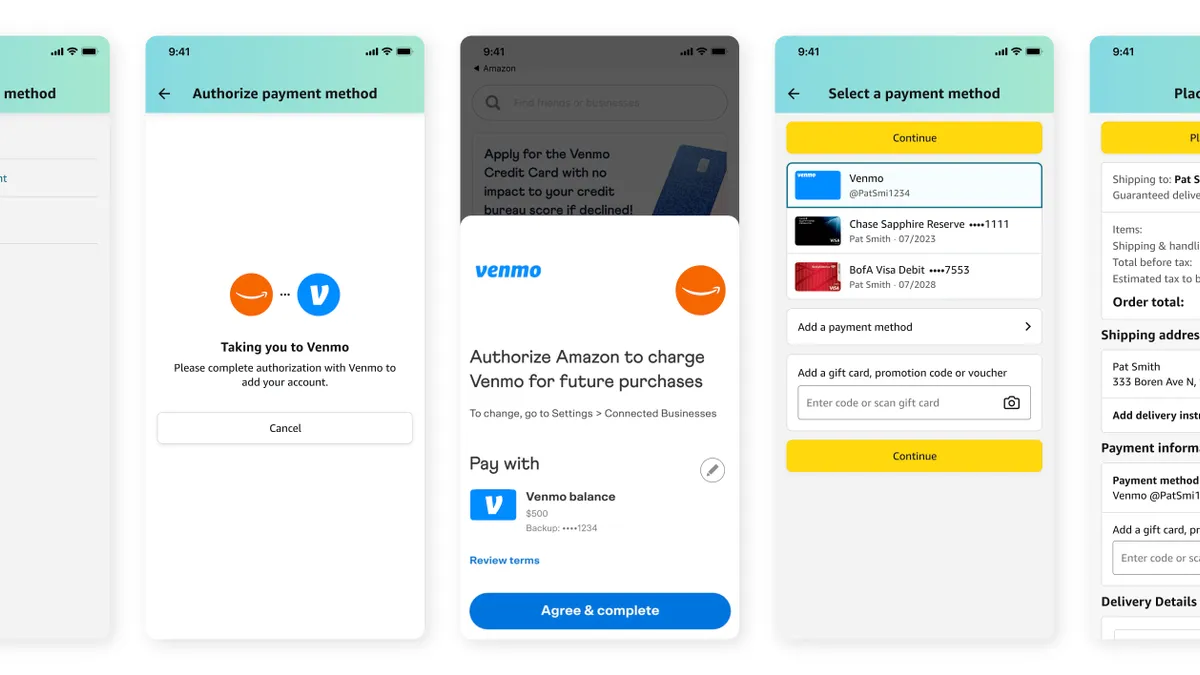

The company’s big goal has been to evolve it into a means of paying for goods and services. Behind the hopefulness in 2021 was a deal with Amazon to add the Venmo button on the e-commerce behemoth’s checkout screen, but that integration didn’t materialize until late 2022 and then Amazon suddenly banished the button late last year, effective in January.

For PayPal investors, it’s been disappointing Venmo hasn’t infiltrated that flow of commerce, said Jason Kupferberg, an analyst with Bank of America, acknowledging it is no easy task. “It’s hard to get people to change the way they pay and people associate Venmo with person-to-person payments,” he said.

Aside from checkout potential, the only income streams for Venmo are from interchange fees tied to the use of credit and debit cards and fees for certain money transfers to bank accounts.

While many big companies, including McDonald's, Starbucks, Domino’s, DoorDash and Uber, offer the Venmo pay button, its 3 million merchant accounts with registered profiles are mainly small and mid-sized businesses.

A key disconnect is that Venmo users don’t store much money on the app, and if there’s no balance, then what’s the incentive to use the app to buy anything, Kupferberg points out.

So, more than a decade after Venmo became part of PayPal, the company is still trying to figure out how to better monetize the business.

Enter Alex Chriss, PayPal’s new CEO, who stepped into his leadership role in September. During an investor conference this month, he acknowledged the company’s failure to make Venmo pay off.

Venmo is “very, very strong, and in a demographic that is highly valuable,” Chriss said at Morgan Stanley’s technology, media and telecom conference on March 4. “I also think we have not done a very good job of monetizing this product.”

Chriss knows this partly because he has observed how his son uses Venmo at college. It makes no sense to Chriss why his son should be splitting the cost of a pizza with his friends via Venmo, but then not pay for the pizza using Venmo. He’s intent on giving such customers the ability to pay with Venmo in “every single situation,” he said at the conference.

In January, the CEO gave a glimpse of how he’ll do that, taking aim at smaller businesses. The company is creating ways for merchants to better market to Venmo users, partly by offering them rewards. It’s also developing a means for merchants to advertise to Venmo users’ networks.

In addition, PayPal this month said merchants will be able to accept Venmo contactless payments via cards and digital wallets tapped on iPhones.

While those changes may incentivize more merchants to accept Venmo payments, it’s less clear how they will change the behavior of the app’s users. For the moment, the new CEO said last month he’ll turn to an American payment classic. To help boost the app brand, PayPal will try to increase adoption of Venmo’s debit card.