Dive Brief:

- The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau’s supervisory actions in the areas of buy now, pay later and earned wage access financing were highlighted for the first time in an agency review of the fourth quarter of last year. Those findings, and some industry reactions, were detailed by the agency in a document included in the federal government’s Federal Register on Jan. 6.

- Some consumers who used BNPL complained to the federal agency that they didn’t receive goods or services under the terms specified, according to the document for the period from Oct. 1 through Jan. 1.

- The edition also detailed other supervisory issues with respect to how earned wage access providers advertised consumer options for tipping and closing accounts.

Dive Insight:

The CFPB noted the rapid expansion of the buy now, pay later and earned wage access options in recent years. In reviewing its supervision in those areas, the federal agency didn’t name any of the companies that it was referring to in the supervision highlights.

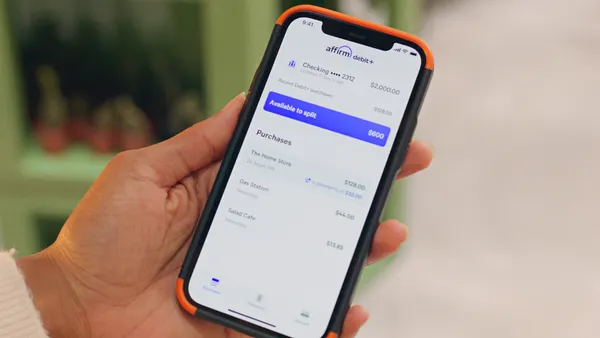

Buy now, pay later services, which are offered by companies such as Klarna, Afterpay and Affirm, allow consumers to pay for goods and services in installments, sometimes without interest payments. With EWA, sometimes called on-demand wages, workers can opt to access their pay ahead of regularly scheduled paydays, often through firms such as DailyPay, Dave and Payactiv, which has a variety of business models.

Last year, the agency implemented new guidelines for oversight of BNPL and EWA. In May, the CFPB proposed an interpretive rule to subject BNPL financing to the same laws that regulate lending via credit cards. And in July, the agency proposed an interpretive rule to apply U.S. lending laws to earned wage access. Providers of BNPL and EWA financing have opposed the new rules.

The question now is whether the agency’s new rules will survive in the next administration, after President-elect Trump takes office later this month. CFPB Director Rohit Chopra has been aggressive in his implementation of rules for new payments areas, but the prior Trump administration demonstrated a lighter regulatory approach in some of those areas.

In the latest supervisory overview, the bureau reviewed what it’s seeing so far in its examinations of BNPL and EWA providers. “Specifically examiners identified multiple violations of law including [unfair, deceptive, or abusive acts or practices] in connection with both Buy Now Pay Later and paycheck advance products,” the fourth-quarter report said.

Consumers who complained about BNPL services not meeting the terms advertised also said that when they contacted the financing provider, including about refunds, they didn’t have disputes resolved in a timely manner.

“These delays were long, with hundreds of consumers deprived of funds for months at a time,” the bureau said in the supervisory overview. “Consumers incurred substantial injury in the form of deprivation of funds that should have been refunded in a timely manner.”

In some cases, consumers were unable to make payments during an investigation by the lender, but then they were suddenly forced to make full payment on an unexpected date, the bureau said.

In response to the agency’s findings, BNPL providers in some cases issued refunds, and they also implemented systems to monitor for delays in responding to consumer complaints, the CFPB said.

The CFPB found that some BNPL lenders and their merchant partners deceived consumers about the terms of the financing.

“The lenders engaged in a deceptive act or practice when its merchant partners ran advertisements on their behalf that included false representations,” the CFPB said in the document. “These advertisements misled or were likely to mislead reasonable consumers, and the deceptive representations were material because they related to the cost and terms of the loans as payment methods.”

In response to the CFPB’s supervision, the BNPL providers responded by contacting merchants to have them revise marketing on their websites, refund overcharges and improving their processes for reviewing such marketing in the future.

The agency also found that BNPL lenders were unfairly denying consumers the option to make payments or receive new financing, while also causing them potentially to use more expensive alternatives or spend time trying to contact the lender to correct the situation.

“The lenders engaged in an unfair act or practice by preventing consumers with loan balances below $1 from making payments, while denying those consumers’ loan applications because of those same balances,” the agency said. “This conduct caused or was likely to cause substantial injury, as it resulted in the lenders denying additional credit for consumers with outstanding balances of less than $1.”

The bureau also noted that it has worked with state regulators on examinations of BNPL firms.

On the EWA front, the agency found that providers of that early wage access were soliciting “tips” from consumers purported to go to “other borrowers” when in fact they simply were added to the companies’ general revenue.

“Under the circumstances and given the misrepresentations, customers lacked the ability to make fully informed choices about whether and how much to tip, which affected the ability to protect their monetary interests,” the CFPB said. “Lenders gained unreasonable advantages when they designed interfaces to take advantage of consumers’ misimpressions.”

The agency’s examiners also cited EWA providers for not letting consumers close their accounts when they had pending debits, after telling them they could close the accounts at any time, and continuing to debit from their other accounts after requested closures.

“Lenders misled or were likely to mislead consumers through confusing and conflicting representations about how to close loan accounts and that consumers could cancel agreements and use of services at any time, the only consequences of nonpayment being placing loan accounts on hold,” the CFPB said.

The CFPB’s examiners also cited “technology failures” that blocked consumers from accessing their funds and the “trouble and aggravation” inflicted on consumers when they tried to fix the problem.