Buy now, pay later providers flourished during the COVID-19 era, when the tide was high with investors awash in capital and consumers swimming in cash. Now, the tide is ebbing, and BNPL companies find themselves flopping around in shallow waters.

This year, soaring interest rates and stubborn inflation have negatively impacted consumers’ spending and their ability to pay debts.

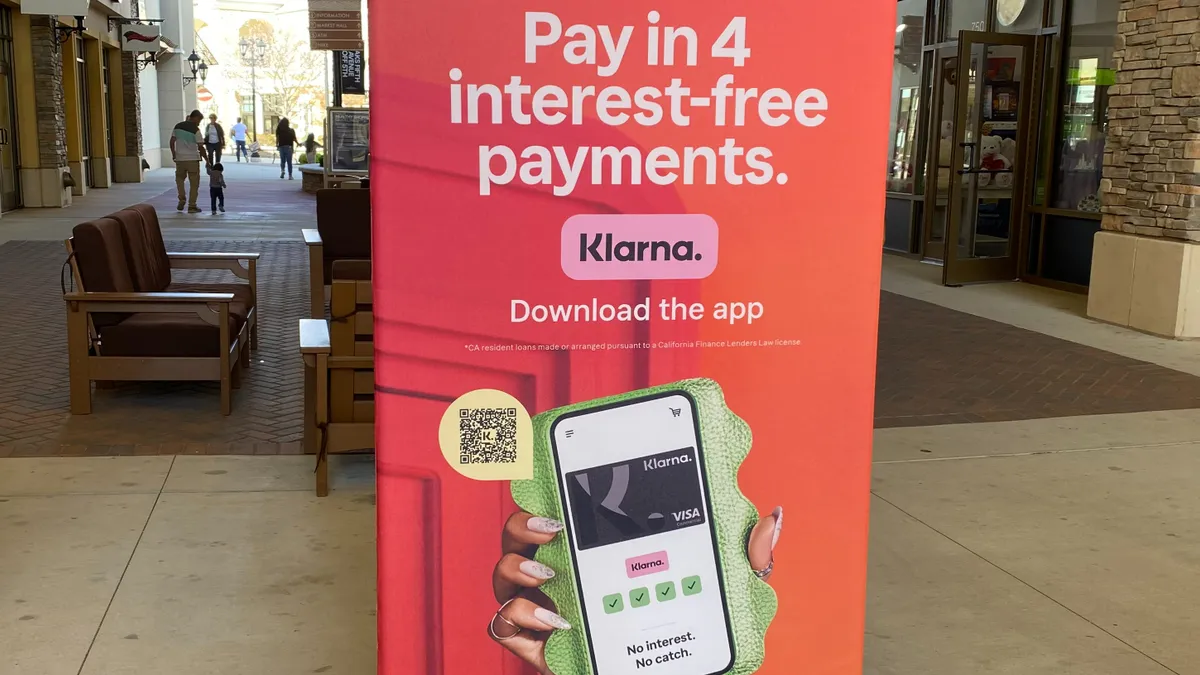

For the big BNPL players, including Klarna, Afterpay and Affirm, the higher rate environment has strained business models, too. They had been raking in venture capital, pursuing new markets and ramping hiring, operating at a loss amid a market share land-grab. Now, venture capital has all but dried up, and the growth-at-all-costs mentality has been swapped for a focus on profits.

Potential regulation has added pressure, with the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau threatening new rules. And new competition from tech giant Apple adds “ecosystem turbulence,” according to an S&P Global Market Intelligence report last month. Other BNPL competitors include digital payments pioneer PayPal and smaller players Zip and Sezzle.

To be sure, consumers are increasingly tapping BNPL for everyday needs, not just wants: The share of e-commerce BNPL purchases featuring groceries shot up 40% during the first two months of this year, according to Adobe Analytics. But to deliver the profits investors want, BNPL companies have tightened underwriting, cut staff, increased prices and pulled back from some markets.

With that change of scenery, the BNPL business model “really comes into question,” said Emily Williams, an assistant professor in the finance unit of Harvard Business School.

“This is pretty typical for these types of fintech-y fads that start to proliferate when times are good and interest rates are low, and then when reality sets in a little bit, it’s not clear that the business model can survive,” she said.

Neither San Francisco-based Affirm nor the Swedish company Klarna are currently profitable (Affirm is a publicly-traded company that reports results while Klarna is privately-held). For the Australian business Afterpay, which was purchased by Square parent Block in 2021, the bottom line isn’t clear, but the company posted losses before the acquisition. A spokesperson didn’t respond to requests for comment on the current financials.

All BNPL providers face an uphill battle in trying to deliver profits amid the current market conditions, consultants and professors said. “The environment heavily dictates where things are going to go,” Williams said.

Avenues of growth

After first gaining traction in European and Australian markets about a decade ago, the installment trend took off in the U.S. during the pandemic’s e-commerce surge. BNPL allows consumers to make a purchase and pay for an item, or service, over a set period of time, often involving four payments with no interest attached.

Buy now, pay later saw explosive initial growth

By 2021, BNPL use ballooned to $24.2 billion in dollar originations, increasing ten-fold from $2 billion in 2019, according to CFPB data shared last September in the agency’s report on the industry.

Last year, total online spending tapping BNPL amounted to $66.4 billion, according to Adobe Analytics data. This year, through May 31, $29.4 billion has been spent online using BNPL, Adobe said.

“The outlook of mass adoption of BNPL was overenthusiastic,” said Matt Risley, partner at venture capital firm QED Investors. Younger consumers’ adoption of it was driven not by consumer preference for BNPL over credit cards, but by the access to credit it afforded younger shoppers, contends Risley, a former chief credit officer and chief financial officer at Klarna.

Use of BNPL is still growing, although it remains a niche product, consultants and investors said. This year, BNPL is estimated to make up about 2.2% of the volume of U.S. e-commerce, compared to 2% last year and 1.7% in 2021, said Zachary Aron, Deloitte Consulting’s global and U.S. banking and capital markets payments leader.

To further expand and fend off Apple, BNPL providers are clamoring for more merchant integrations to increase their visibility at checkout. Square merchants have the option to offer Afterpay services to customers.

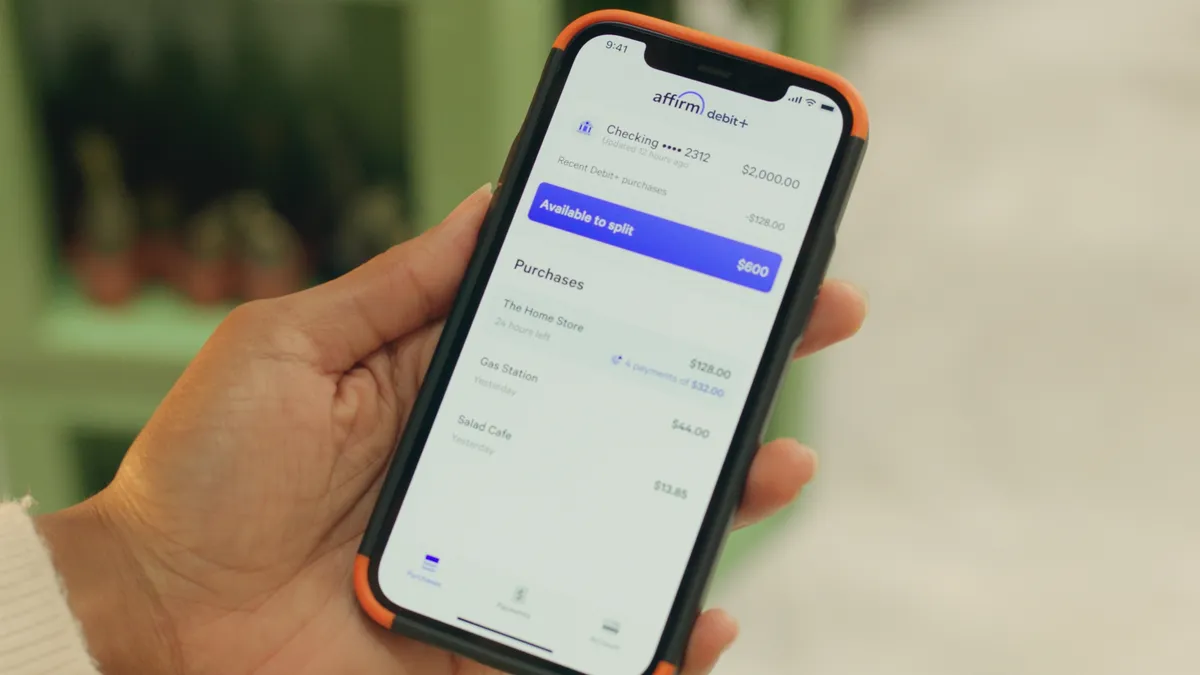

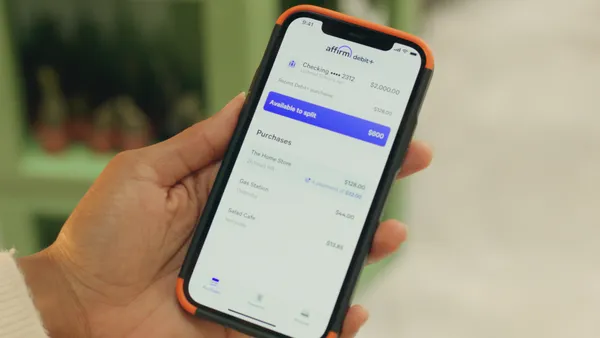

BNPL providers have also established direct-to-consumer connections, nudging customers to use their services at any merchant through apps or debit cards, with the goal of being used more frequently and in stores.

Because BNPL players have nearly saturated subprime and younger consumer segments, they’re probably evaluating how they can appeal to older consumers with better credit histories, said Kevin King, vice president of credit risk and marketing strategy at LexisNexis Risk Solutions. Long-time credit cardholders, however, may have little need or incentive to switch to BNPL.

One-quarter of the U.S. population has tried BNPL, and the industry is seeing more growth from repeat users than newcomers, according to LexisNexis Risk Solutions data.

For Klarna, further growth in the U.S. – currently its largest market by revenue – remains an intense focus, said David Sykes, the company’s chief commercial officer. Klarna counts 36 million customers in the U.S., with an average age of 36, and its fastest-growing generational segment is baby boomers. Sykes declined to estimate Klarna’s current share of the U.S. market.

While Gen Z and millennial consumers continue to be “primary” BNPL users, “the number of Afterpay orders made by Gen Xers and boomers increased 16% and 12%, respectively,” as of March, according to a Square report published June 20. Block declined to make an executive available for an interview.

Still, BNPL companies have moved away from customer growth at all costs. With calls for profits growing louder, providers have had to reassess strategies, including shuttering operations in certain markets. Affirm pulled out of Australia earlier this year.

Some have also sought to restructure their installment products, by adding interest, increasing rates on interest-bearing loans or shifting into longer-term loans. As the funding environment has become tougher, Affirm has raised its maximum annual percentage rate on interest-bearing loans in recent months. Affirm also declined to make an executive available for an interview.

Klarna and Affirm have each made employee cuts in the past year, and BNPL providers have tightened underwriting as consumers’ financial situations have become shakier.

Approving enough loans to satisfy merchants, while limiting credit to curb BNPL losses, has always been a “tricky” aspect of retail risk management, “but it is dramatically more so for BNPL,” said King, whose company is a unit of RELX Group.

That’s partly because the fees that merchants pay for BNPL transactions are higher than what they pay in interchange fees for credit card payments. BNPL providers justify the higher charge by promising that consumers will add more items to their shopping “baskets” and be more likely to finalize the purchases, but also because BNPL has established itself as a form of credit with a low bar for approvals, King added.

Regulation looms large

BNPL’s rapid growth hasn’t gone unnoticed by regulators, and it’s only a matter of time before the CFPB takes action to monitor companies, attorneys and professors said.

“Regulators want more visibility into this,” said Williams. She and colleagues have conversed with regulators about the university’s research findings issued last year that flagged BNPL risks.

In its own BNPL report last September, the CFPB identified concerns with consumers overextending themselves and companies engaging in data harvesting. The bureau said it was considering “interpretative guidance” to ensure BNPL providers are held to the same standards as credit card companies. BNPL isn’t covered by the Truth in Lending Act. The CFPB has also expressed concern with consumer disputes of BNPL transactions.

CFPB guidance could address BNPL marketing or opt-in consent, or it could relate to data surveillance, legal professionals said. Another sticking point for the CFPB: the lack of BNPL data being furnished to credit reporting agencies. Affirm CEO Max Levchin in May said his company is working with FICO to create a unique scoring model for BNPL.

The CFPB signaled this month that it plans to propose a larger participant rule that could increase regulation of big tech companies active in consumer payments, such as Apple, Google and PayPal. The CFPB has also said it plans to use the “risks to consumers” provision under the Dodd-Frank Act more extensively. The CFPB could rope in BNPL companies by way of either, said Eamonn Moran, senior counsel at law firm Norton Rose Fulbright specializing in consumer financial services.

“The CFPB seems to be using supervisory authority in a more expansive and robust way than in the past,” said Moran, a former counsel at the CFPB’s Office of Regulations. Being brought under the bureau’s supervisory jurisdiction could significantly impact how BNPL companies manage operations and compliance, he said.

There’s also regulatory movement at the state level: California has addressed BNPL in its credit regulations, and other states including Massachusetts and Oregon have weighed BNPL regulation, too.

One possible reason the CFPB hasn’t acted yet: The bureau may be waiting to see how the market shrinks as more companies face increased pressure.

“Right now, we have a lot of people playing around in the same space, competing for the same dollars and they’re all carrying a lot of overhead,” said Ed deHaan, a professor at the Stanford Graduate School of Business, who has studied BNPL and its effect on consumers. “My gut tells me that this can’t persist and we’re going to have to see some consolidation.”

All eyes on profits

Financial institutions have sought to create their own BNPL products, rather than risk acquiring a BNPL company, given regulatory concerns and the lack of profits, said Capco Managing Principal Daniela Hawkins.

Turning a profit is going to be a requirement for BNPL providers, consultants said. “It's very, very clear that markets are looking for something different now,” Sykes said. “It's not about future growth; it's about profitability today.”

Klarna was last profitable in 2018, and is pledging to achieve that again in the second half of the year. Still, its annual loss last year widened over 2021, to 10.4 billion Swedish kronor, or about $1 billion. In the first quarter of this year, the company halved its loss, compared to the same quarter a year earlier.

As for Affirm, a spokesperson pointed to Levchin’s comments in the company’s May quarterly shareholder letter that says Affirm intends “to grow responsibly” as it strives to become profitable, on an adjusted operating income basis, by the end of the fiscal year ending June 30.

Affirm’s net loss widened for fiscal year 2022 to $707.4 million, from $441 million, according to its annual filing with the Securities and Exchange Commission. The company reported a $205.7 million loss in its fiscal third quarter ending March 31.

“They’re all having to find religion when it comes to, ‘how do we make this more profitable?’” King said.

With that in mind, Klarna is focused on more than just the short-term loan product: Sykes stressed that Klarna has sought to expand its focus beyond BNPL, incorporating marketing services, for example.

“When we think about the future, and we think about the value that we have, it's not just dividing the purchase into four,” Sykes said. “It's, how do you help create a new customer for a retail partner?”

A Block spokesperson didn’t respond to requests for comment on Afterpay’s profitability status. Prior to Block acquiring Afterpay for $29 billion in 2021, Afterpay “historically generated net losses,” Block’s most recent annual filing noted. Afterpay’s gross merchandise volume jumped 18% to $5.6 billion for the first quarter, compared to the year-earlier period, according to its earnings report.

Risley expects the BNPL providers will ultimately survive as industry pricing competition moves away from what is currently a desperate battle to lure merchant customers. As the BNPL market rationalizes, that could end up being a smaller group of providers.

“It feels like it’s settling into a mature industry with not-so-great margins,” Risley said.

Correction: This story has been updated to specify the status of Klarna as a privately-held company.